Linked Data 101 - What's with all the URIs?

This article is part of the Linked Data 101 series

UR-WhatNow ?

URI is an acronym for Uniform Resource Identifier, which is one of those whole names that tells you nothing at all. A URI is simply a particular way of writing a name for a thing. A common kind of URI is the URL (Uniform Resource Locator) where that name is actually treated as an address and provides you with a way to look up the identified thing. The address of a webpage like this one is a URL.

People are so used to seeing tabular data with numerical IDs, and so used to only ever seeing URIs as “things you click on to go to a website” - that the use of URIs as data record identifiers can be a stumbling block for a lot of people when we talk about linked data. Don’t worry, you’re not alone! Let’s just take baby steps through the idea of using URIs, and by the end of the post you shouldn’t still have that nagging feeling of confusion when you see URIs all over the place in linked data.

The identifier

Each record in your data needs some way to identify it, we might be used to seeing this as a numerical ID or a more complex code, but we all are comfortable with the idea that in order to group all the values that attach to a record (e.g. title, description, location) we need a way to identify that record as a “thing”. In relational databases, the ID of one table (such as products) has a “primary key” that is then referred to as a foreign key from another table, thereby linking the two records.

It makes sense then, that in the far wider Web of Data, using URIs as those primary and foreign keys makes complete sense. Arbitrary codes or numbers have no way of containing the information needed to locate that data on the web. In particular it makes a whole load of sense to use HTTP URIs for a couple of reasons. Firstly HTTP URIs form a neat, globally managed system where you can buy a domain and then manage the content of that domain as you see fit. As long as everyone sticks to the rule of only creating new URIs in domains that they control you can happily make new URIs under the domains that you control without having to worry about name clashes. Secondly HTTP is also a protocol - it defines a way in which an application can take the HTTP identifier and use it to request some information from a server - and this is where the Web part of the Web of Data happens.

404 - I’m just making up web addresses!

In most tutorials and walkthroughs you’ll find people using identifiers such as http://data.example.org/category/pets or similar. Yep, they don’t “go anywhere” if you put them into your web browser. In a sense, that is perfectly fine, the URI is an identifier not an address.

However, if your goal is to populate a Linked Data browser on an open data portal then of course you’ll need to use your data portal’s address as the root domain, the rest of the URI depends on how you’d like to present your resources to the outside world. If you really want you could present every resource you keep http://yourdataportal/1, http://yourdataportal/2, http://yourdataportal/3, http://yourdataportal/4 etc, but I strongly advise against it! You’ll find it a lot easier to navigate and work with your data using URIs that are fairly easy to read by humans as well as computers.

URIs are everywhere

You’ll have seen that the RDF is made up of triples:

| Subject | Predicate | Object |

|---|---|---|

| The identifier | The link between the identifier and some property of the resource | The value of the property |

| Must be a URI | Must be a URI | Can be a literal or a URI |

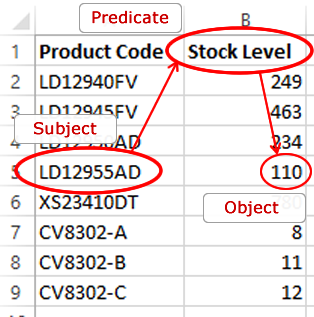

Think of how you read information out of an Excel spreadsheet. For example, if I want to find the stock level of a product, I look up the product, read along the column headers until I see the column for stock level, then read the relevant value out of that column for the product’s record.

In this example the triple would look something like:

<http://data.example.org/products/LD12955AD> <http://data.example.org/stockLevel> "110"^^<http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema#integer>

The way we are writing triples here, the three parts are separated from each other by spaces and angle-brackets (<>) are used to wrap URI identifiers. You will also see that the value at the end of the line (“249”) is followed by a double-caret (^^) and another URI - this last URI is specifying the data type of the value. In effect saying that the string “249” should be processed as an integer. This is an example of a triple with a literal (in this case the literal is the integer value 249). We can also create triples that have a URI as the object:

<http://data.example.org/products/LD12955AD> <http://data.example.org/manufacturer> <http://contoso.com/#company>

We can see why URIs must be used as subjects, and can be objects, what about the predicates? Why not just use text labels to describe properties of a resource such as “stock level” or “manufacturer”? Well, without using URIs we would miss out on the core power of the Web of Data - a way of being able to embed our data with the information that we are talking about the same concepts that another data publisher is describing in their data.

That’s exactly what the second blog post in this series is going to concentrate on - predicates and vocabularies - stay tuned!

This article is part of the Linked Data 101 series